Europe's online source of news, data & analysis for professionals involved in packaged media and new delivery technologies

Holography - Quo Vadis?

Has anything happened in the past three years that might bring holographic discs closer to reality? MEGUMI KOMIYA, Head of Research at Globalcom, takes stock of the latest developments, pinpointing promising advances.

Walk around a hologram image that is floating in space and it's sometimes hard to convince yourself that it is not real. Your conscious mind knows that there is nothing there, your hand can pass through it without resistance, but subconsciously your imagination wishes that it could have more substance than just a trick of the light. Holographic data storage has something of the same characteristics.

For most of the past decade, which wishful thinkers once dubbed the 'Era of holographic storage', it seemed that the pioneering dreams would come true. Blue lasers were incorporated into consumer products and now was the time for the 'next big thing', a plausible development roadmap to extend the capacity of a 12 cm disc from megabytes to gigabytes and beyond. Holographic data storage was going to make this possible and after 20 years of R&D, it emerged from the labs in the early part of this century. Although it seemed unlikely to be suitable for replication in the millions needed for home entertainment, many observers thought that it could be the perfect archiving and data storage medium.

Magnetic storage density [and therefore the cost per gigabyte] has fallen rapidly since 1992, when according to IBM the cost per gigabyte was over $1,000. This figure dropped to $4 per gigabyte by 2001 and today one gigabyte of storage on a consumer computer hard drive costs around 20 cents. Seagate, the leading manufacturer, talks about solid state drives for less then 10 cents per gigabyte in the foreseeable future. In comparison, over the same period the capacity of a 12 cm recordable disc failed to keep pace with these developments, a truth that moving from red to blue lasers failed to conceal.

Today's dual-layer DVD-RAM drive with its 8.5 Gbyte capacity is barely big enough to store the data from an iPhone. A Blu-ray rewritable disc makes almost no dent in the terabyte or more of magnetic data storage available to home computer users. Fifty gigabytes seems insignificant when compared to the amount of data that digital HD videographers can create in a single summer holiday. We are all creating more and more data but where will we store it? Magnetic disks wear out, crash and leave users wishing they had backed up their data. On to what?

It may be probable that Blu-ray is the end of a long line of 12 cm rewritable discs using technology that originated with the Compact Disc. If this is the case, what will replace it? In the struggle to commercialise holography, companies have come and gone with the same short-lived reality as a holographic image. Some big names in consumer technology, including Polaroid, Toshiba, Sony, 3M, Bell Labs, Hitachi and RCA, have invested many millions in optimistic start-ups, in the hope that the fruits of pure research could be turned into tangible profits.

The economy of Longmont, Colorado, prospered and then faltered as first InPhase, in 1999, and then Optware Corporation, in 2005, arrived in the city and then struggled as they tried to make holographic storage work reliably. Promise frequently came close to reality, with prototypes regularly displayed at exhibitions and conferences. But cracks always began to show and the anticipated 500 Gbyte disc became the 300 Gbyte disc, reportedly because of the need for massive error correction when holographic discs were partnered with other players. Terabytes moved to the distant horizon, as the simple act of swapping discs from one player to another could lead to the loss of data. Importantly, there is still no agreed standard.

Flurry of developments

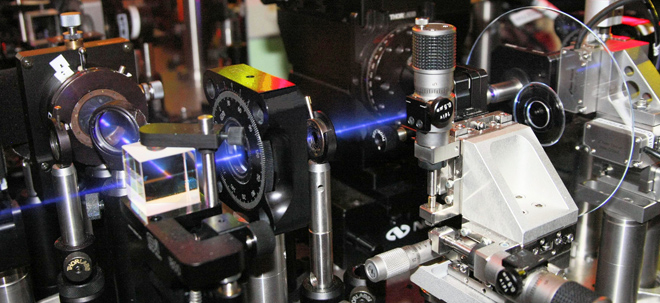

Bob Auger provided an outline of the technology behind holographic discs in this magazine in 2006 and from a practical viewpoint little has changed since then. Holography is fundamentally a three-dimensional technology, storing data in blocks (or pages) of around a megabit at a time. When everything works, over ten thousand pages of data can be written each second and over 30 Mbytes per second can be delivered to the host computer, compared to the Blu-ray disc, which maxes out at under 5 Mbytes per second. More important than the raw data rate, is the fact that data is written and read in a parallel fashion, much closer to the multi-core parallel processing architecture of the modern computer.

So, has anything happened in the past three years that might bring holographic discs closer to reality? There have been many rumours, including one that the Sony PS4 will feature a holographic drive. There have also been announcements like Sony's 7-layer 500 Gbyte holographic disc, which appeared in November 2007 and has not been heard of since. In fact, the technology that was announced in Singapore focuses light on seven different layers and Sony themselves referred to it as a multi-layer recording technology, rather than holography.

In 2002, Polaroid spin-off Aprilis Inc. announced that it was to supply holographic media to companies in Korea and Japan, and talked of delivering 200 Gbyte discs in quantities of 10,000 units a month. The company's assets were later acquired by Dow Corning as DCE Aprilis in August 2006 and then sold to the Korean company STX Force-Tec in May 2008. STX Aprilis now concentrates on licensing its portfolio of more than 130 US and foreign granted and pending patents in holographic technology and media products.

There have been encouraging developments in other areas of holographic media, such as the stability of the recording medium. Data is stored in the disc, not on layers like a dual-layer DVD but within the thickness of the space between the protective outer covers. The plastic material used for holographic discs is very stable, but it can shrink when the laser passes through it. Although this is only by 0.23%, it is enough to upset the relationship between the zeros and ones of digital data, making it hard to recover the information that was written. Progress on this problem was announced in January 2009 by the University of California in Santa Barbara. By replacing the small molecules in the plastic polymer with larger, branched ones, physical distortion is reduced to just 0.04%, which may bring the terabyte disc a little closer.

GE in pole position

But the most promising announcement of 2009 (so far) comes from GE Research in New York. A team led by Brian Lawrence, who heads GE's Holographic Storage programme, has been working to create holographic media that can be written and read using the same 405 nm lasers that are used for Blu-ray discs. GE, which also owns NBC Universal, has been working on holographic storage for over six years and researchers have been very focused on making the technology easily adaptable to existing optical storage formats and manufacturing techniques.

The GE Research breakthrough was the ability to increase the reflectivity of the microscopic patterns in the recording medium so that they can be read by a low power laser. Importantly, the higher reflectivity indicates that, when scaled down in size, the holograms would correspond to the pits created using standard DVD or Blu-ray optics. Brian Lawrence explained that these enhanced reflectivities will enable the storage of up to 500 GB of data in a single CD-size disc. And maybe even allow the eventual replication of holographic discs…?

This development from GE could be the milestone in the creation of 'micro-holographic' discs, which ultimately will deliver that ephemeral terabyte of data storage on a 12 cm disc. This could arrive just in time for NHK’s Super Hi-Vision, with its uncompressed bit-rate of 24 Gbits per second – or around 28.8 Tbytes per hour.

Whatever uses the new discs may be put to, maybe finally it will be possible to touch a real holographic product, one that will last the promised 100 years, rather than disappear like the prototypes that have come and gone over the past decade.

Megumi Komiya, Head of Research at Globalcom, has been tracking the communications, IT and media industry for over 20 years. Previously, Megumi was heading strategy consultancy at Nomura Research Institute in London. Contact: megumi.komiya@dvd-intelligence.com

Story filed 12.10.09