Europe's online source of news, data & analysis for professionals involved in packaged media and new delivery technologies

ANALYSIS: Watching Video in the Multiscreen Era

It shouldn't be news to anyone in the television and video industries that their customers or 'viewers' have been finding lots of new ways to watch their content over the past few years. If it is, they should probably find a role which doesn't involve knowing how their industry is changing, argues DAVID MERCER, Principal Analyst at Strategy Analytics.

Hopefully it will also come as no surprise that viewers are able to engage or 'interact' with TV and video content using new devices and technologies. For years the television industry tried, and largely failed, to establish interactive TV services and applications (using the TV screen) as a mass market opportunity. Instead they have arrived in the past few years 'via the back door', namely PCs, smartphones and tablets.

As our research has shown, the number of people watching video on different devices has exploded over recent years. By the end of 2013 27% of Europeans were watching internet video on their TV screen, nearly double the level two years earlier. The proportion of internet video users of smartphones had also doubled, and the percentage of people using tablets grew from 4% to 14%.

Watching and engaging with video using second screen devices are now the two main areas of activity which define the broad field of multiscreen video. Except that I prefer not to use the term 'second screen', since it implies some gradation of significance and it is not at all clear how that can be defined, or indeed whether it should be. The more progressive operators such as BSkyB are recognising that they should plan on the basis that all screens are equally important from a strategic perspective, although this approach is certainly difficult for more traditionally minded broadcasters to accept.

So the multiscreen transition is happening around us, but it seemed clear to us that no one had yet defined and quantified the variety of behaviours and attitudes which were emerging as a result of these relatively new mass market technologies. With this in mind we developed a research programme which would provide deeper insight on the different types of behaviour related to multiscreen video. Using a technique called latent class analysis, we investigated more than 40 related survey responses from more than 6,000 television viewers across the US and Europe. The research investigated five broad areas related to video and TV:

- How important is TV in people's lives and how do they watch it?

- How do people go about discovering video content?

- To what extent are people communicating about and around TV and video?

- Which people are using multiscreen applications?

- How do attitudes to advertising vary?

The latent class technique identified six segments. The largest group we describe as Couch Potatoes, a term we chose deliberately to reflect the fact that this segmentation has a link to this traditional mode of watching TV. This behaviour is still very much alive and well and accounts for 33% of all respondents. This group is focused on the TV screen when they are watching shows and movies. They will not be distracted by other gadgets, although these may be available in the household, and they never communicate with anyone who is not in the room about what they are watching. They are unlikely to use social media related to video and television content, and while a few may be using online video services and catch-up TV, in general they are unlikely to do anything if they miss a TV show when it is broadcast live. Demographically, and not surprisingly, this group is weighted towards older age groups and two thirds live in one- or two-person households.

The next group, accounting for 12% of the total, are Couch Chatterers. These people are characterised by their high levels of voice and text communications around video and TV content. Television and video are important in their lives and they will also engage in some social media activity around TV, but they do not follow TV shows and movies using Twitter. They do not use online video or catchup TV services and while the segment is weighted towards females (58%-42%) it is relatively evenly represented across all age groups.

The second biggest group are TV OTTers. These people have lower than average levels of interest in TV in general but they like to watch specific shows and are very likely to try to find a show if they have missed it on TV. TV OTTers are very likely to go online (or 'OTT') to find a show they have missed, and some will also use the VOD service from the TV service provider. But apart from the online video activity, TV OTTers are less likely to engage in multiscreen communications around video and TV shows and they rarely phone or text people about what they are watching. The demographic profile of this group is close to the population as a whole but weighted slightly towards females.

The remaining three segments are multiscreeners. Moderate Multiscreeners represent 11% of the population, and are more likely than average to engage with TV and video using social media as well as communicating with friends about shows. However they will not use Twitter to follow TV shows and movies. This group is weighted towards younger age groups and have the highest share of students.

Indifferent Multiscreeners are the fifth group and also account for 11% of the total. This group is characterised by its lower interest levels in television in general; they are the most likely group to go 24 hours without watching TV. They are the least concerned about missing TV shows, but when they do watch they are highly engaged: nearly all of them comment frequently on shows using social media sites such as Facebook and they also follow content using Twitter. They are more likely than average to use 'new TV devices' like smartphones, tablets and PCs. This group is the most heavily weighted towards males (60%-40%) and also the most likely to be single.

Finally we come to Manic Multiscreeners, which are the smallest segment (7% of the total). This group is most active in every characteristic included in the study. It is interesting to note that this group scores highest in considering TV as a primary source of entertainment, at the same time as being most likely to consider it a 'huge waste of time'. They also agree most strongly that TV is background to other activities - 'the TV is on but I am not really watching it'. One explanation for this apparent discrepancy could be that they feel unable to control their, and their household's, behaviour. It is also worth noting that these households are most likely to include children, for whose benefit the TV is often, presumably, switched on.

Manic Multiscreeners are most likely to use service provider VOD and OTT online TV and video services. They are also most likely to communicate about TV using every means possible. Every Manic Multiscreener claims to follow TV shows using Twitter. Demographically the group tends towards the 25-45 age groups and is slightly weighted towards males. They have the highest incomes and are more likely to be households with children.

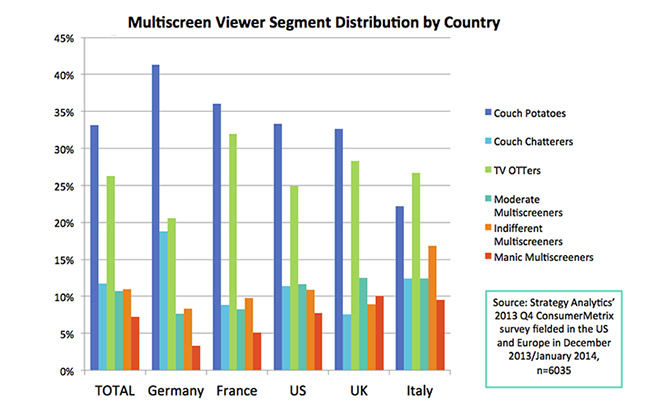

These segments exist in all five countries included in the survey, although in slightly different proportions. Germany has the highest proportion of Couch Potatoes, and the lowest number of Manic Multiscreeners. This reflects the fact that Germany has been relatively late to adopt new OTT video services, and it will be interesting to see how Netflix's recent arrival will affect the segment weightings.

When we summarise the findings we see that traditional behaviours, as defined by Couch Potatoes and Couch Chatterers, are now in a minority across the population as a whole. Emerging behaviours account for 55% of the TV/video audience, although true multiscreeners, who engage in most or all activities to some degree, account for less than a third of the total.

An important conclusion from this analysis is that we should be careful when using traditional demographic segments to describe video and television related behaviour. The TV industry in particular is wedded to classic age and gender groups, but our work shows that their effectiveness can be limited. As an illustration, when we examine the classic 'Millenials' group (15-35 year olds in this case), we find that they exhibit behaviours of each of the six segments. 16% of Millenials are Couch Potatoes and 14% Couch Chatterers. So companies which assume that using social media or online video services, for example, will reach this part of the audience are missing out on 30% of the under-35 population.

One of the other key findings relates to Twitter. The social network has developed a very high profile and Twitter itself has been focusing on building relationships with the television community. Our research shows, however, that only two segments are using Twitter in relation to television content: Indifferent Multiscreeners and Manic Multiscreeners. Together they comprise 18% of the audience, so more than four in five people do not use Twitter to follow TV. Content owners and distributors should be aware that they are targeting only two specific segments by working with Twitter.

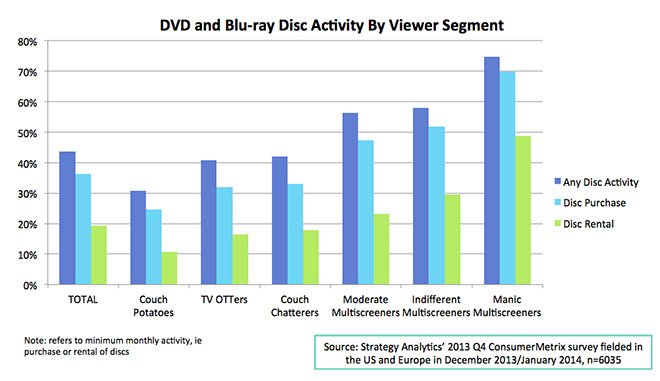

What does all this mean for the disc industry? When we look at disc rental and sell-through relative to the viewer segments, we find a very similar set of relationships as with other video and TV behaviour. Manic Multiscreeners are significantly more active in all types of disc activity than any other segment: 75% rent or buy at least monthly, and 70% alone claim to buy a DVD or Blu-ray Disc at least monthly. Nearly half are still regularly renting discs, in spite of their strong affiliation with other video and television activities as noted earlier.

By contrast, Couch Potatoes show the lowest levels of disc activity: 31% rent or buy monthly, with 25% buying and 11% renting. So it seems that usage of DVDs and Blu-rays correlates strongly with the overall multiscreen TV segmentation. At one level this should not be surprising, since watching video discs is essentially another form of multiscreen TV behaviour. On the other hand, we might have assumed that segments which are heavily engaged in watching online video or using a TV VOD service might be those which have reduced their disc activities accordingly.

We have not yet examined time-series evolution of the segmentation so we cannot confirm with certainty the degree to which Manic Multiscreeners, for example, have reduced, or indeed increased, their disc usage over time. But we can say with certainty that, in spite of their high levels of online video and VOD usage, they are still also heavily engaged in DVD and Blu-ray Disc usage and to a much higher level than other segments.

Another way to examine the data is to look at disc users overall. As a benchmark, 44% of all respondents buy or rent a DVD or Blu-ray Disc at least monthly. While their activity is low relative to other segments, because of the size of the Couch Potato segment they still account for nearly a quarter of all disc users. TV OTTers account for a further 25%, in spite of the fact that they are heavy online video users. And although multiscreeners are engaged in a variety of emerging video activities, overall they still account for 40% of all disc users.

In conclusion the DVD and Blu-ray Disc communities should not assume that OTT TV and online video automatically exclude certain segments as opportunities for their own businesses. Indeed, they can now appreciate which segments of their disc-using customer base are likely to be most receptive to business and marketing opportunities related to online and social media activities.

We will be gathering further evidence on the evolution of these segments over time as we roll out further waves of the analysis over the coming months.

Contact: Dmercer@strategyanalytics.com; Twitter: DavidMercer_SA

This is one of several editorial features included in the forthcoming DVD and Beyond 2015 magazine. Reserve your free copy.

Story filed 25.12.14