Europe's online source of news, data & analysis for professionals involved in packaged media and new delivery technologies

FEATURE: Monetising strategies to mitigate falling video spending

The strategy of ‘mining’ studios’ back catalogues exhausted the category. The years of burning through ever older catalogue titles to generate easy revenues in a booming market are over. Instead, today’s content owners need to learn to ‘farm’ their catalogues and thus maintain revenues in a stable market, in the same way as most other mature business sectors, says RICHARD COOPER, Senior Analyst at Screen Digest.

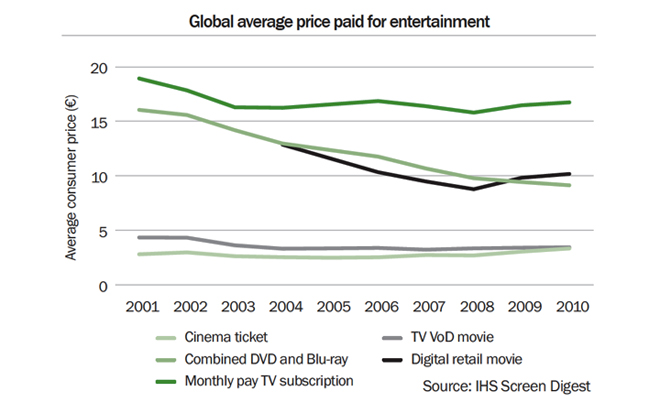

The home video industry revenues have been in decline since global consumer spending on video peaked in 2004 at €40.7bn ($50.7bn). In 2010, consumer spending on buying physical video formats has fallen, a further 4.6% to €29.6bn ($41.3bn), IHS Screen Digest analysis indicates. However, in volume terms the trends have been much more positive: the number of video units sold continued to grow for a further three years peaking in 2007 at 2,289m, 217m higher than in 2004. Since then unit sales to consumers have fallen on average by only 1.1% per year. The reason for the difference between the two rates of decline is the persistent downward trend in average prices.

There is, of course, an argument that the price decline itself drove those additional years of unit sales growth. However, the 39% growth in the number of households becoming DVD enabled worldwide over this period indicates strong continuing consumer interest in home video. Furthermore, additional price declines didn’t help reverse the unit sales declines experienced from 2008 to 2010.

The movies and TV content that drive the video industry are available through an ever increasing number of distribution channels, including cinemas, pay TV and video-on-demand (VoD) and digital delivery. According to IHS Screen Digest analysis, industry revenues are growing in every one of these, while average prices are largely stable and in many cases increasing year on year despite the competition between them.

The price of cinema tickets has historically risen in line with inflation, but in recent years the digital 3D boom has accelerated the rise in average ticket prices.

In the Pay TV space not only has the average monthly subscription price for basic services climbed ahead of inflation but so has the price of transactional VoD. On a global level, monthly average revenue per user has fallen only 12% in the past decade.

Digital video encompasses both digital retail and rental models and the price of each was originally designed to undercut those used in the physical video space. However, as these markets became increasingly dominated by device-driven services (iTunes, Xbox and PlayStation) transaction prices have increased. This was in part driven by a transition to high-definition, a trend notably absent from the average price of a physical video purchase, despite the launch of Blu-ray in 2006.

What distinguishes these models from the physical video business is that one way or another they are addressing an audience which is captive in some way; geographically in the case of cinema or else by service or device. As a result competition is driven by what’s on offer rather than what it costs.

The same cannot be said for physical video. The competition between video retailers for consumer footfall has led to more and more aggressive discounting on physical video. Many content owners, where such practices are not prohibited by law, report seeing retailers regularly advertising consumer prices that are below cost price even after the inclusion of ‘marketing spend’ (effectively a further discount to list price). Retailers are prepared to sell at a loss to gain a competitive advantage; such is the consumer pulling power of video.

What enables some models to increase price?

Both cinema and the various forms of TV delivery have clear time windows associated with the channel; theatrical runs may last just weeks while a title’s availability on pay per view may last a few months. And crucially, consumers understand that consumption of content through these channels is a time limited offer, ‘take it or leave it’ offer.

Although the legitimate digital market replicates the physical market and thus contains no time limited offers, consumers choosing to access content in this way may only compare prices within the ecosystem rather than being able to shop around.

In contrast, the physical purchase model developed by content owners and retailers presents few limits to consumers. This was, of course, the dynamic which made physical video historically such a unit sales success. A significant proportion of all the home video titles ever released remain available to purchase years after their initial release, and the vast majority of homes in most developed markets (85-95% according to IHS Screen Digest research) have the requisite hardware needed to access this content.

Furthermore retailers aim to ensure that almost all the titles they choose to carry remain in stock at all times;, whether this is just the top 100 performing chart and catalogue titles in some supermarkets, a few thousand top performers for video specialists or tens of thousands of titles for internet retailers (who need just one copy of each to remain in stock).

With the exception of new releases, where initial sales are still driven by the desire to own content as soon as it becomes available (and frequently at a discount for week one), this constant availability has robbed the physical video market of opportunity to create a sense of urgency in consumers. In addition retail practices have effectively trained consumers that by delaying their purchasing, titles will ultimately become available at a far lower price.

The ‘always available’ model doesn’t work in practice

There may be thousands of titles available, but the vast majority of sales can be attributed at any one time to just a few thousand top performing titles. This group of titles consists of new and recent releases, perennial catalogue titles and titles currently being price promoted. They form just a tiny fraction of the 70,000 video titles available.

It is perhaps a self fulfilling prophesy that the number of titles required to fill allocated supermarket shelves and those of specialist retailers struggle to extend beyond those few thousand top performing titles; retailers can after all only sell as many titles as they can stock. But even for internet retailers, the ‘long tail’ remains in many ways a myth, with the majority of sales still focused on the top performers.

Price promotion is used to distinguish titles

The difficulty for retailers and consumers alike is the wealth of content available. Once a title’s new release sales peak is over and it falls from the front of consumers’ minds it becomes part of the vast and growing content catalogue. Catalogue now comprises a bewildering number of titles, far too great a choice for most retailers and consumers to make an informed selection.

Any event that brings individual titles back into the conscious mind of retailers and consumers helps to drive sales of those titles. The cinematic and home video release of sequels is a well recognised driver for awareness; the release of Disney’s Tron Legacy in cinemas will no doubt see an increased demand for copies of the original 1982 Tron. IHS Screen Digest research indicates that even cover-mounting (giving discs away for free or at rock bottom prices with magazines and newspapers) deep back catalogue titles simulates the sales of those titles at retail, simply by raising awareness of the title in consumers’ minds.

However, the simplest way to attract attention to specific titles – and the industry’s default setting when it comes to promoting DVD and Blu-ray –is to discount it to a point at which the low price itself becomes the title’s distinguishing feature.

Content owners must manage catalogue

There are, of course, other ways to distinguish catalogue titles that don’t require discounting, though they do require an acceptance on the part of the industry that not every title should always be available. It might be argued that lack of availability would lead would consumers to piracy, but even here research suggests most piracy tends to concentrate on the top performing titles.

Examples of the strategy can readily be seen; Warner recently removed three of its classic movie titles , Singin’ In The Rain, What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? and Camelot from sale in anticipation of their respective 60th, 50th and 45th anniversaries in 2012. Disney also regularly uses moratoriums on key animated titles. These titles are released for a short time only creating limited windows of opportunity for consumers to buy, which drives a sense of urgency to purchase.

This strategy effectively positions catalogue titles as 'new release' products, allowing them to be sold at a higher price than a film their age would otherwise command. This approach could easily be adopted for any number of blockbuster titles and, following Disney’s example, need not coincide with specific anniversaries.

The strategy would not work for all titles; there are plenty whose time has simply passed. However, withholding strong catalogue titles from sale in this fashion would enable studios to better maintain the strength of their release slates. Furthermore, content owners would have much more control over the price commanded by these titles, helping to improve consumer price perception in the video market.

RICHARD COOPER is a Senior Analyst in Screen Digest's Video team where he is responsible for the ongoing development of the online Video Intelligence service, including designing, constructing and maintaining the detailed computer models that underpin Screen Digest's video forecasts. His other responsibilities include tracking the expanding Blu-ray Disc replication sector and monitoring trends in emerging markets.

It is one of the topics addressed at the forthcoming PEVE conference in London, 10-11 March 2011. Click here for details.

Story filed 02.01.11